For weeks, Solangel Contreras raced.

The Venezuelan migrant and her family of 22 trudged through the dense jungles of the Darien Gap and hopped borders across Central America.

They joined thousands of other migrants from across the Hemisphere in a scramble to reach the United States-Mexico border and request asylum.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

They raced, unsure what changing migratory rules and the end of a pandemic-era border restriction, Title 42, would mean for their chances at a new life in the U.S.

But after missing that cutoff, robbed in Guatemala and crossing into Mexico shortly after the program ended Thursday night, Contreras, 33, had only one certainty in her mind: “We’re going to keep going.”

Confusion has rippled from the U.S.-Mexico border to migrant routes across the Americas, as migrants scramble to understand complex and ever-changing policies. And while Title 42 has come to an end, the flow of migrants headed north has not.

From the rolling mountains and jungles in Central America to the tops of trains roaring through Mexico, migrants from Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti, Colombia, Nicaragua, Ecuador and beyond push forward on their journeys.

“We’ve already done everything humanly possible to get where we are,” Contreras said, resting in a park near a river dividing Mexico and Guatemala.

The problem, say experts, is that while migration laws are changing, root causes pushing people to flee their countries in record numbers only stretch on.

“It doesn’t appear to be the case that this is going to curb the push or pull factors for migration from Central America, South America and other parts of the world,” said Falko Ernst, senior analyst for International Crisis Group in Mexico. “The incentives for people to flee and seek refuge in safer havens in the United States are still in place.”

For Contreras, that push came after her brother was killed in Ecuador for not paying extorsions to a criminal group. The family had been living in a small coastal town in the south after fleeing economic crisis in Venezuela two years earlier.

Others, like 25-year-old migrant Gerardo Escobar left in search of a better future after struggling to make ends meet in Venezuela like Contreras’ family.

Escobar trekked along train tracks Friday morning just outside Mexico City, with 60 other migrants, including families and small children. They hoped to climb aboard a train migrants have used for decades to carry them on their dangerous journey.

Escobar was among many to say he had no clue what the end of Title 42 would mean, and he didn’t particularly care.

“My dream is to get a job, eat well, help my family in Venezuela,” he said. “My dream is to move forward.”

Despite misinformation prompting a rush to the border last week, analysts and those providing refuge to migrants said that they don’t expect new policies to radically stem the flow of migrants.

Title 42 allowed authorities to use a public health law to rapidly expel migrants crossing over the border, denying them the right to seek asylum. U.S. officials turned away migrants more than 2.8 million times under the order.

New rules strip away that ability to simply expel asylum seekers, but add stricter consequences to those not going through official migratory channels. Migrants caught crossing illegally will not be allowed to return for five years and can face criminal prosecution if they do.

The Biden administration has also set caps on the amount of migrants allowed to seek asylum.

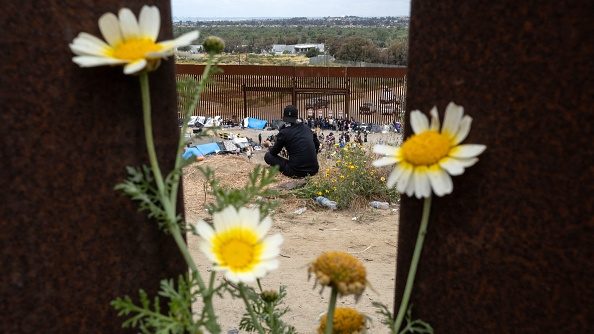

Scenes From the US-Mexico Border as Title 42 Ends

At the same time, Biden is likely to continue American pressure on Mexico and other countries to make it harder for migrants to move north.

Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs Marcelo Ebrard said they don't agree with the Biden administration’s decision to continue to put up migratory barriers.

“Our position is the opposite, but we respect their (US) jurisdiction,” Ebrard said.

Yet in a news briefing on Friday, he announced Mexico would carry out speedier deportations, and that it would no longer give migrants papers to cross through Mexico.

While the new rules likely won’t act as a strong deterrent, Ebrard and the head of a migrant shelter in Guatemala said they saw a drop in the number of migrants they encountered immediately following the rush on the U.S. border. Though the shelter leader said numbers have been slowly picking up.

Ernst, of International Crisis Group, warned that such measures could make the already deadly journey even more dangerous.

“You’ll see an increase in populations that remain vulnerable for criminal groups to prey on, to recruit from and make a profit from,” he said. “It could just feed into the hands of these criminal groups.”

Meanwhile, Contreras continues trucking forward alongside many other migrants, even with no clear pathway forward and little information about what awaits them at the U.S. border.

It’s worth it, she said, to give a better life to small children traveling with them.

“We’ve fought a lot for them (the kids)," she said. “All we want is to be safe, a humble home where they can study, where they can eat well. We’re not asking for much. We’re just asking for peace and safety.”

——

Associated Press journalists contributed from Marco Ugarte in Huehuetoca, Mexico, Edgar H. Clemente in Tapachula, Mexico, Mark Stevenson in Mexico City, and Colleen Long in Washington. Janetsky reported from Mexico City.