His Army stint complete after serving in Afghanistan, Damian Daniels left Alabama to begin a new life in Texas. He bought a house, enrolled in college and supported the Black Lives Matter movement. Black himself, Daniels was working to start a new business when paranoid hallucinations began last month and a brother sought help from police.

Shot dead by officers who were sent to aid him, Daniels was buried Friday on Sept. 11, the anniversary of the date that sent him down the path to war.

Relatives gathered at Alabama National Cemetery, about 30 miles south of Birmingham, to mourn a death they are still trying to understand.

“A call for help should never result in the loss of life,” brother Brendan Daniels said in an interview beforehand.

The shooting is still under review in San Antonio, where a sheriff defended officers’ actions but a county leader said the killing never should have occurred. Grand jurors will review what happened, a prosecutor has said.

Brendan Daniels said it took only a matter of days last month for Damian to go from seeming normal to being on edge, so he called deputies to check on his brother. He was stunned to get the call back from authorities on Aug. 25 saying the 30-year-old man was dead, shot on his front porch by a sheriff’s deputy in San Antonio.

Daniels’ funeral was set for the 9/11 anniversary in remembrance of the day that landed him in a war zone after the terror attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. Her face covered by a mask adorned by stars, mother Annette Watkins sat in the front row holding a folded U.S. flag.

Texas News

News from around the state of Texas.

An Alabama native, Daniels grew up in Montgomery and graduated from George Washington Carver High School in 2009. He signed up for the military like two of his brothers and served in Afghanistan before getting out and deciding to settle in San Antonio.

“I think he drove through it one day,” brother Brendan said. “He liked it there and chose to stay.”

Property records show Daniels bought a suburban home last year, where he lived by himself. He often carried a handgun — Texas’ loose gun laws were an attraction to the state, his brother said — and got by on disability payments from Veterans Affairs plus earnings from driving for ride-share services, his brother said.

Daniels suffered from a mild case of post-traumatic stress disorder linked to his military service, but he hadn’t shown signs of more severe mental problems, family attorney Lee Merritt said. Relatives said the man seemed fine until about Aug. 22, when he suddenly started making odd comments.

Brendan Daniels, who lives in Colorado, said his brother didn’t have any pets but texted him a warning about a fat black cat with spots. Damian called and would only whisper, with the explanation being: “He can hear us,” his brother said. Another time, Damian told his mother that someone was in his house massaging his legs and “trying to get him to fight,” the brother said.

Worried after his brother said he “needed help,” Daniels contacted the sheriff’s office. Officers made multiple trips to the house in two days; during one, Daniels told them it may be haunted.

On Aug. 25, during their fourth trip to the house, deputies found Daniels near the front door. A photo taken from police video showed Daniels with a bulge at his waistband from a gun and a pained expression on his face.

“When you look at my brother’s face, you can tell it’s distorted. He’s tired; he’s beat,” Brendan Daniels said.

A struggle began after a 30-minute discussion, Sheriff Javier Salazar said, and a deputy fired twice, hitting Daniels in the torso. Deputies apparently tried to make the man seek mental health care against his will, his brother said.

The sheriff said officers did their best in an imperfect system that typically sends armed officers, not mental health workers, to confront people in the throes of a mental crisis.

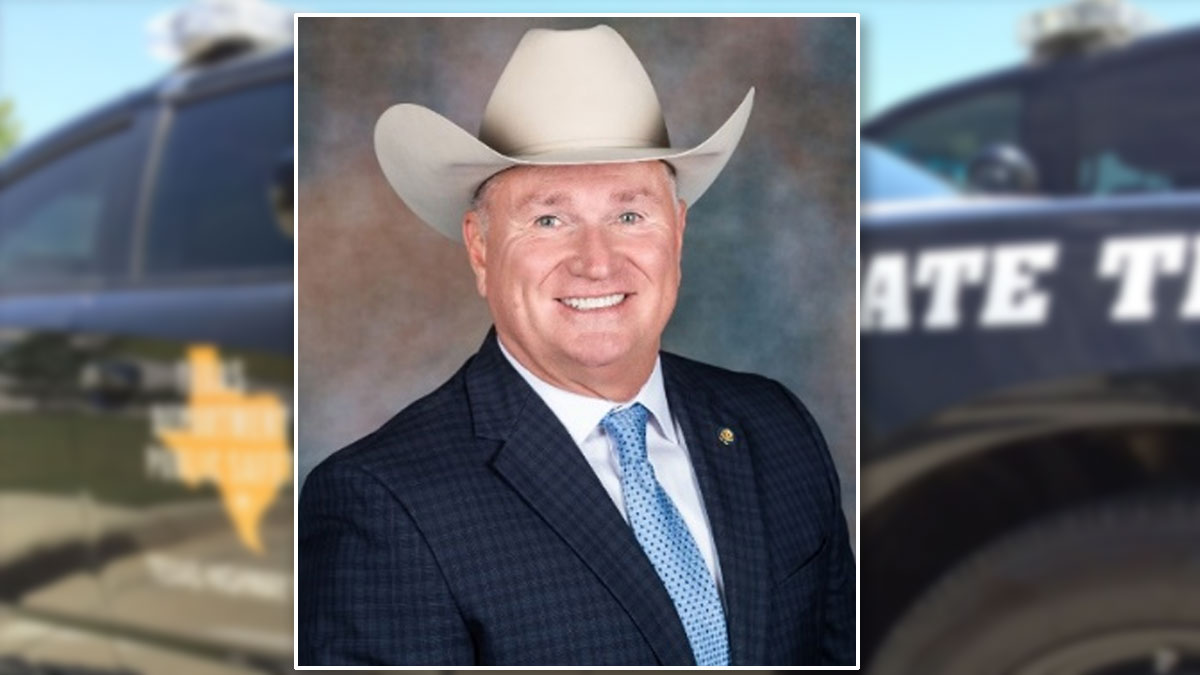

“I do believe law enforcement is overused in incidents like this nationwide. I think we’ve come to rely on our first responders for a lot of things, and one of those things is mental health,” Salazar told a news conference.

County Judge Nelson Wolff said Daniels had mental problems, not a criminal history, and shouldn’t have ended up dead. He has asked the county manager to recommend changes so mental health professionals rather than deputies are sent to face people with “known mental health issues.”

“Based on the information I have, … I believe this incident should have never happened,” Wolff said.

Brendan Daniels said he doesn’t know what caused his brother’s swift mental decline. It could have been the deaths of a sister, his father and an uncle this year, he said, or it may have been the stress of starting college to study business while also working on a used car business the brothers were planning.

Dozens of protesters, some aligned with the Black Lives Matters movement, have demonstrated against Daniels’ killing in San Antonio. While it’s unclear whether race was a factor in the shooting, statistics show Black people are more likely to be killed by police than whites.

One way or the other, Brendan Daniels knows this: His brother’s first episode of mental illness left him dead at the hands of police.

“It’s a sad story all the way around,” he said.