A Collin County mother has found the strength to talk about losing her son to fentanyl, she tells NBC 5’s Maria Guerrero that parents have to stop thinking, “not my kid.”

As local and federal law enforcement continue the fight against fentanyl, a Collin County mother has found the strength to speak publicly about losing her son to the synthetic drug.

It’s been nearly seven months since Gayle Meeks got the call that will forever mark her life.

“My son T.J.’s best friend contacted me and said, 'Are you OK?' And I looked at the text and thought, 'Why wouldn’t I be OK?' And he said, 'Can I call you?' And he called and he told me that T.J. passed away,” said Meeks. “I was in shock. I screamed like this is not real.”

Her funny, adventurous daredevil of a son Thomas James Nevant who loved poker, elephants and the color orange died suddenly of a fentanyl overdose.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

Meeks never imagined her son would join the statistics related to fentanyl. Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids in 2020 were 18 times more than the number reported in 2013, according to the CDC.

“It’s your child,” she said through tears. “You have to write an obituary. You have to decide, are you going to have an open casket. These are things that parents shouldn’t have to do for their children and it’s absolutely heart-wrenching and it’s the worst pain I’ve had in my entire life. It’s a pain you can’t describe, and I don’t want other parents to feel this way.”

Fentanyl is approved for treating severe pain, typically for cancer patients, in a hospital setting. It is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, according to the CDC.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

The United States Drug Enforcement Administration’s administrator Anne Milgram describes fentanyl as ‘the single deadliest drug threat our nation has ever encountered.’

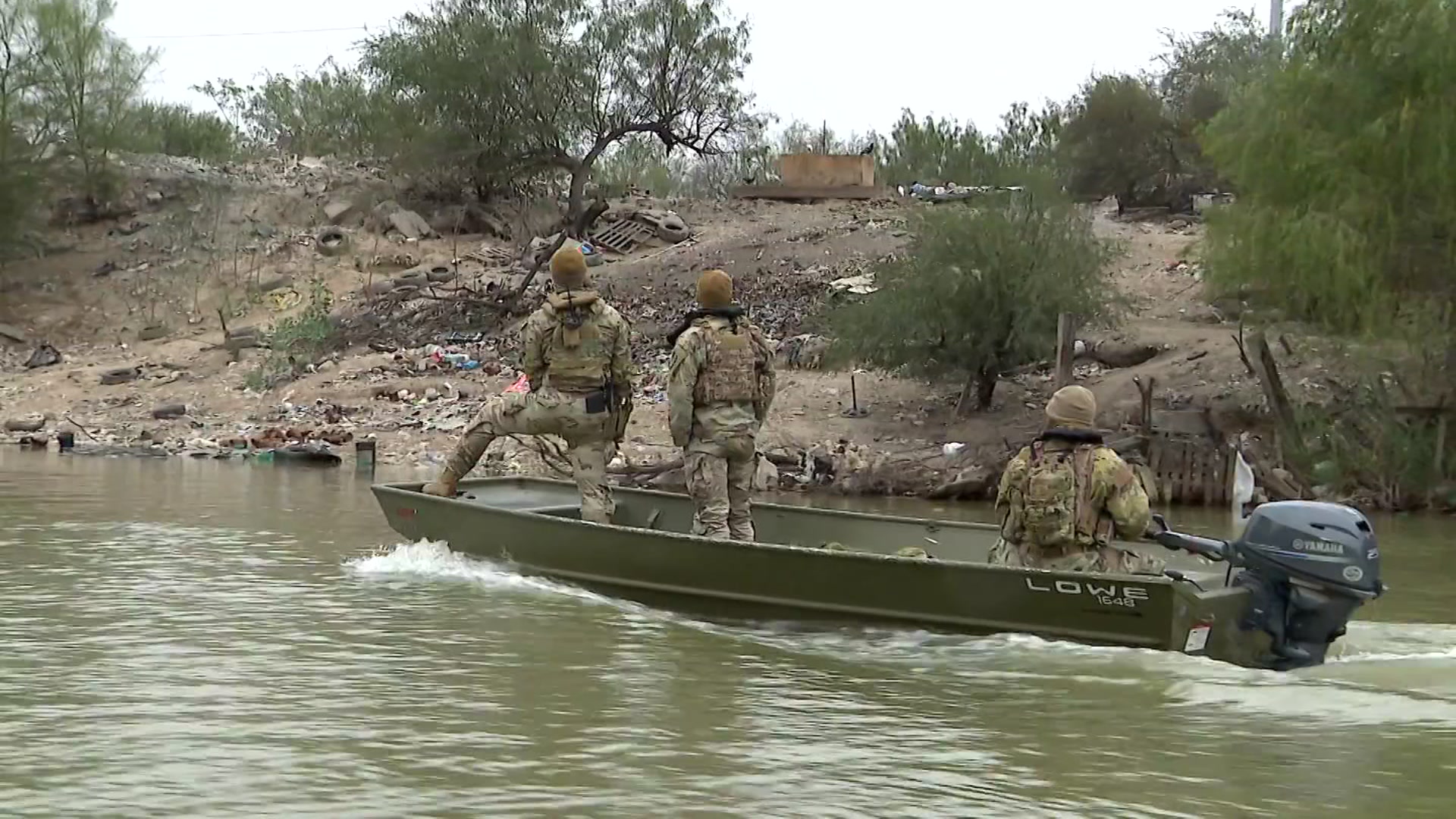

Meeks is honoring her son’s memory by speaking out about the addictive synthetic opioid that Mexican drug cartels, with the help of ingredients sent from China, can easily manufacture into counterfeit pills and smuggle into the U.S.

The DEA stresses there is no “quality control” during the manufacturing process, so pills often contain lethal doses of fentanyl.

“They do not measure well and so they just look at those that die as the price of doing business,” said Meeks. “It’s horrible and it’s a pain I never knew existed and I’d like to get the word out there so that parents don’t have to feel this way and so that senseless deaths don’t have to happen.”

Meeks says in T.J.’s case, the 24-year-old was living with five friends in a Plano house last September.

He had previously struggled with drug addiction but was recently feeling better and more himself.

T.J. was on the verge of a promotion at work and was excited about the future, even hoping to get married, she said.

He was sitting on the couch when his friends were going to bed on September 24, 2022.

“There was one friend that said he was breathing a little heavy,” said Meeks. “Just deep breathing and he just thought ‘I hope he didn’t take anything.’ He didn’t think anything else because who thinks you’re going to die.”

T.J.’s friend went to bed.

“The next morning [T.J.] was still sitting on the couch. He was eating a hamburger and he was literally sitting there with a hamburger in his mouth. Dead,” she said.

An autopsy revealed the 24-year-old only had fentanyl in his system, six times the lethal dose of the drug, said Meeks.

It is unclear where T.J. got the pill and whether he knew the pill was fentanyl.

Meeks believes he may have sought out morphine because her son had recently been hospitalized with a kidney stone and given morphine.

Whatever the reasons, Meeks’ journey to healing is focused on making ‘fentanyl’ as known as COVID-19.

“I didn’t even know about fentanyl,” she said. “I’ve obviously learned a lot in the past seven months.”

NBC 5 asked the head of the Dallas division of the DEA to provide an update on their fight against fentanyl in DFW.

“Our biggest challenge overall is just continuing to identify those responsible for trafficking it and bringing it to our neighborhoods,” said Eduardo Chavez, special agent in charge of the DEA Dallas Field Division.

Chavez is hopeful this is a war they can win, thanks to increased cooperation between agencies and increased awareness of the drug’s danger.

“We have now been able to take advantage of the fact that fentanyl, through its ingenious delivery method of a pill, is getting the attention of community groups, of school districts, of parishes,” he said. “We need everyone’s help.”

Chavez agrees it should be a household name by now, “Because fentanyl is not that other neighborhood’s problem or that other family’s problem. There is no stereotype.”

The agency has noticed a shift since October in people who are struggling with addiction intentionally seeking out fentanyl, in particular the rainbow-colored counterfeit pills trying to pass off as legitimate medications.

Authorities stress there is no "quality control" when it comes to the tablets, while one could contain only a trace of fentanyl another tablet might only contain fentanyl.

Chavez says they are also anxious about the coming weeks and months for teenagers across the region and country.

“You’re having a lot of exams and STAAR tests and even celebrations like graduation, prom,” said Chavez. “It just lends itself to maybe taking a little more risky behavior.”

Chavez and Meeks urge parents to open their eyes and have frank discussions with their children, whatever their age, even if it may feel awkward.

“If you have to scare your kids, scare your kids because maybe they won’t be in Heaven and you won’t be in pain,” said Meeks.

“One experiment could kill them. One.”