- President Biden announced a student loan forgiveness plan Aug. 24 that would eliminate up to $10,000 of federal debt for most borrowers, and up to $20,000 for Pell Grant recipients.

- Various analyses indicate the extent to which low-, middle- and high-income borrowers will benefit. Most suggest low- and middle-income earners get the biggest benefit.

- Data peculiarities and future financial benefits that would disproportionately accrue to certain borrowers make an exact accounting nearly impossible, according to economists and education experts.

Determining who benefits most from student loan forgiveness — the poor, middle class or wealthy — may sound like a straightforward exercise.

But an exact calculation is difficult, according to economists and education experts. Aside from challenges related to the available data, future financial benefits that will accrue to certain borrowers are nearly impossible to model, they said.

However, the issue carries particular importance as the public weighs the merits of President Joe Biden's Aug. 24 announcement that he would cancel up to $10,000 of federal student debt for most borrowers, and up to $20,000 for a subset of debtors. The relief is also limited to those who make less than $125,000 per year, or married couples or heads of households earning less than $250,000.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

In remarks following the announcement, Biden said 95% of borrowers — 43 million people — would benefit from the debt relief plan. Nearly 45% of borrowers, or almost 20 million people, would have their debt fully canceled, he said.

But which borrowers stand to benefit most?

Money Report

White House plan assesses individuals, not households

The White House issued a chart breaking down the distribution of total dollars forgiven by three income groups. It shows that 87% of the money would go to those earning less than $75,000 a year. None would flow to individuals earning more than $125,000.

Leveraging this data, Biden said the plan would target poor and middle-class people — "families who need it the most."

This is true in at least two senses: The policy sets an income cap for forgiveness, ensuring the wealthiest households can't participate. And recipients of Pell Grants, a type of financial aid for lower-income families, qualify for double the maximum relief, or $20,000, relative to other borrowers.

But the White House analysis measures income per individual, rather than at the household level. Let's say each spouse in a married couple earns $70,000 a year — they'd have $140,000 of joint household income, but would count among the group earning below $75,000 in the White House income analysis.

The Biden administration felt an analysis of individuals would be more accurate than households since U.S. Department of Education data doesn't indicate if a borrower is married, according to a White House official.

'This isn't a giveaway for the rich'

A few institutions have conducted independent analyses that gauge overall household impact. Most estimate low- and middle-income households will get the bulk of benefits, but diverge on those groups' precise share of overall forgiveness dollars.

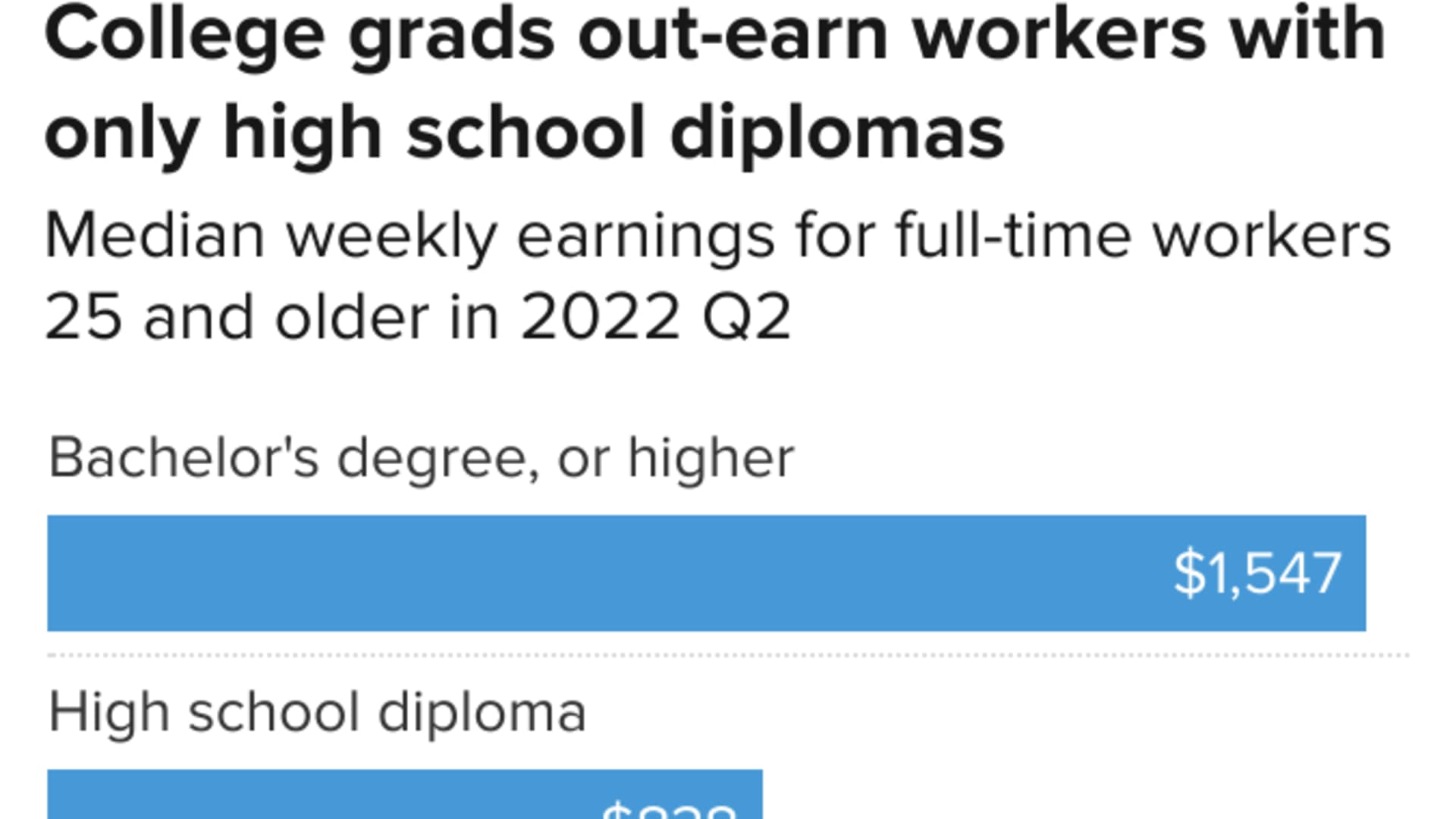

Economists at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School estimate that households with annual income below about $82,000 would receive the bulk — 74% — of the total forgiveness funds. These families fall in the bottom 60% of wage earners.

Those in the bottom half of earners would get about 55% of forgiveness dollars, according to a separate Penn Wharton analysis for CNBC.

"This isn't a giveaway for the rich," said Kent Smetters, a professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

"Slightly more relief" accrues to the bottom half, largely due to the "Pell Grant bonus," Smetters said.

"But it does not especially target lower-income households as much as other transfer programs," he added, using the earned-income tax credit as an example of an existing policy with better targeting to poor households.

About 95% of the total benefit flows to households with less than $150,000 of income, Penn Wharton found.

A White House official said the Penn Wharton study supports its basic finding that the vast majority of benefits flow to low and middle earners.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute, in a separate study, found that a smaller share — 51% — of total debt forgiveness would flow to the bottom 60% of households. JPMorgan defines this group as having income below $76,000 a year.

Middle class could see 'biggest effective income boost'

Roughly two in three of the lowest-income borrowers would have their federal student debt fully erased, the JPMorgan study found. Black and Hispanic borrowers would be more likely to have their debt fully forgiven than white borrowers, according to the analysis.

Biden's policy would give lower-income households with student debt the "largest proportional cut in debt payments," relative to mid and high earners, according to a separate Goldman Sachs report published Aug. 25. Most lower-income households don't have student debt and therefore won't get a benefit, though, according to the study.

"We estimate that middle-income households will receive the biggest effective income boost from the announced debt forgiveness plan," the analysis said.

'There's no perfect data' for forgiveness impact

So, what to make of all this? In short: It's hard to make definitive statements about what income groups will get what share of the benefits.

For one, each analysis uses different data sets that yield different results. The Penn Wharton estimate, for example, leverages data from the Education Department and the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances. Due to particulars of that Fed survey, while it factors in a parent's student debt it perhaps wouldn't capture the debt of a recent graduate living at home with those parents, according to economists.

Meanwhile, JPMorgan's analysis uses credit bureau and Chase banking data. The analysis assumes all borrowers with $125,000 to $250,000 of income are married, for example; the bank's data suggests that's true for the "vast majority" of these borrowers, but the assumption skews the distribution of benefits toward wealthier households, according to the analysis. Using data on bank customers may also leave out some lower earners, economists said.

"There's no perfect data; it doesn't exist," said Dominique Baker, an associate professor of education policy at Southern Methodist University. "Even the Department of Education doesn't have perfect data."

Consider other oddities such as this: The government issues Pell Grants to students based on parents' income; as long as a borrower's income is less than $125,000, they'd qualify for the Pell Grant forgiveness "bonus" based on their parents' lower incomes from years prior, Smetters said.

There's also the issue of which "income" to consider for an analysis of the forgiveness benefits, according to Matt Bruenig, an economic policy analyst and president of the People's Policy Project.

For example, economists can choose to examine parents' current income, a student borrower's current income, or a student's expected future lifetime income, Bruenig said. These sorts of data assumptions yield different results.

"We want to do an analysis we can't really even do," Bruenig said.

'There's this entire shift in the financial lives of people'

There are also a host of financial benefits from loan forgiveness that would mostly accrue to low and middle earners but which can't be captured in these data analyses, according to education experts.

Contrary to popular belief, borrowers with the smallest debts are the most likely to default on their student loans, said Susan Dynarski, an education professor at Harvard University. These tend to be low- and middle-income borrowers, she said.

Defaults negatively impact credit scores, which may then negatively impact homeownership, hurt job prospects and raise costs for other lines of credit, she said.

"All of this isn't measured" in income analyses, Dynarski said. "I think it underestimates the benefits of forgiveness, especially for the small loans."

More from Personal Finance:

Don't refinance your federal loans while you wait for student debt forgiveness

Borrowers in these states may owe taxes on student loan forgiveness

GOP could bring a legal challenge to block Biden's student loan forgiveness plan

Forgiving these relatively small balances may mean less overall federal dollars flow to these borrowers — but forgiving their debts would likely have an outsize impact.

"There's this entire shift in the financial lives of people," Baker of Southern Methodist University explained.

Many borrowers are in default due to failures of the student loan system itself, such as errors among student loan servicers relative to income-driven repayment plans, Dynarski said. Fixing these errors by forgiving debt is likely worthwhile, even if it means some wealthier households who "don't need it" also get a benefit, she explained.

"For people with small loans who are being harmed to get out of this system, I'm OK with a few middle-class people getting forgiveness," Dynarski said. "I consider it a cost of doing business."