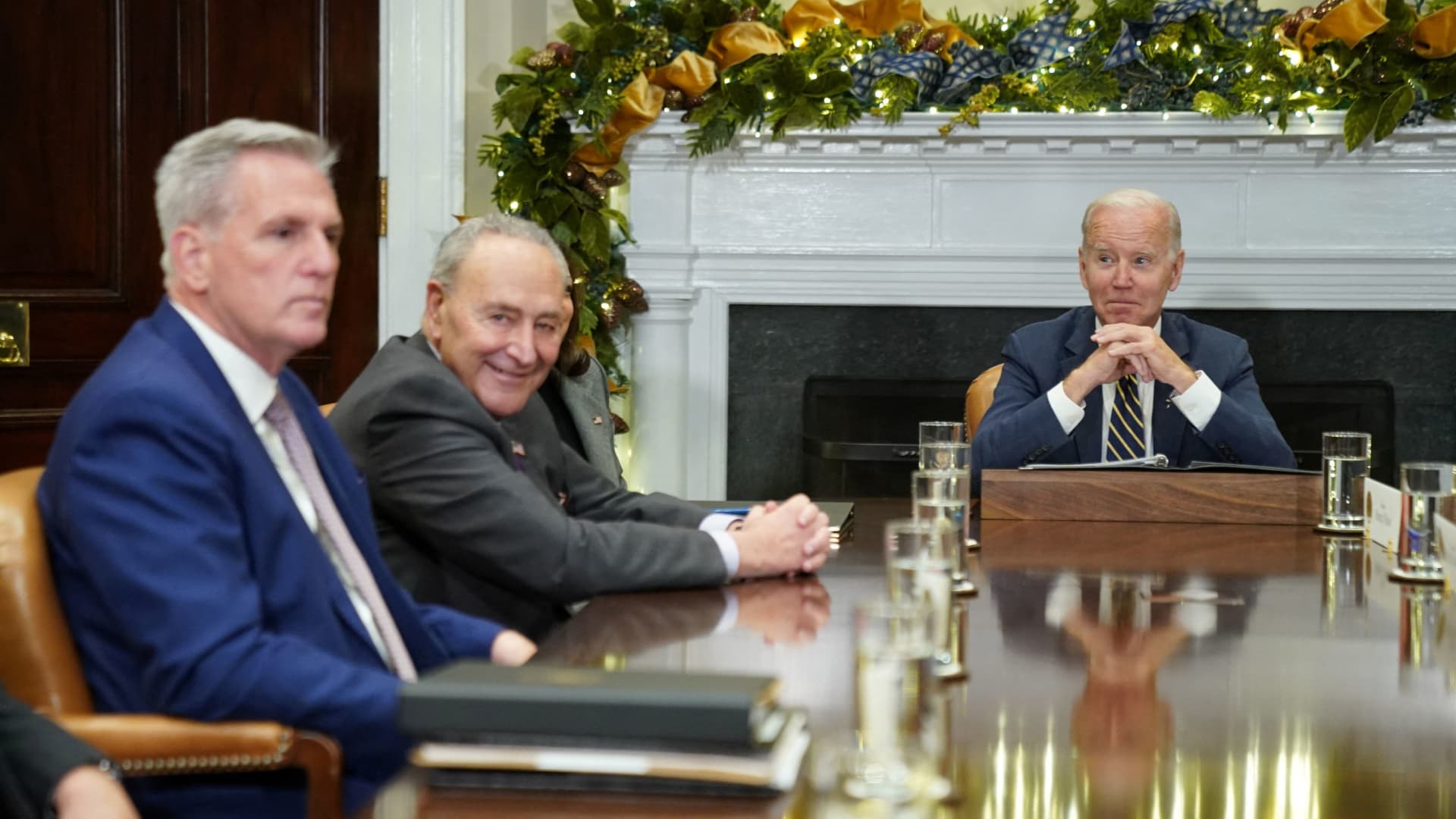

House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy speaks to reporters following a meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden and other congressional leaders at the White House in Washington, U.S., November 29, 2022.

- President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy will meet Wednesday afternoon to discuss the looming U.S. debt ceiling deadline.

- The meeting is a key test of whether the Democratic president and the Republican House speaker can build a working relationship.

- But while McCarthy is preparing for a negotiation, the White House is battening down the hatches for a fight.

- Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has estimated Congress may need to suspend or increase the debt limit before early June to avoid a first-ever default on U.S. debt.

WASHINGTON — As President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy prepare to meet Wednesday afternoon to discuss the looming U.S. debt ceiling deadline, both sides are waging an increasingly bitter messaging battle, one that offers a glimpse of how the next few months of political knife fighting could unfold.

On Wednesday morning, McCarthy held a closed meeting with his Republican caucus in the Capitol to preview his sit-down with the president. Leaving that meeting, the speaker said its purpose was "just education" for his members, according to Bloomberg News.

"If [Biden] doesn't want to play politics, and if he wants to start negotiating, let's sit down and start negotiating where we could come together for the American public," said McCarthy.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

But while the House speaker says he is preparing for a negotiation, the White House is battening down the hatches for a fight.

A White House memo circulated Tuesday sought to portray the 3:15 p.m. ET meeting as a showdown, one between a Democratic president who will protect Social Security, Medicare, health insurance and food stamps, and a House Republican majority that will demand cuts to these programs in exchange for helping Democrats avoid a catastrophic default on the nation's debt.

The Treasury Department has started to take extraordinary steps to keep paying the government's bills, and expects to be able to avoid a first-ever default at least until early June. Failure by Congress to raise or suspend the debt limit by then could wreak economic havoc around the world.

Money Report

McCarthy has consistently said cuts to the popular Social Security and Medicare programs are "off the table" in any debt ceiling talks. But Democrats point to past GOP plans and proposals to argue that the party ultimately aims to slash those benefits.

The three-page memo from National Economic Council Director Brian Deese and Office of Management and Budget Director Shalanda Young said Biden plans to ask McCarthy for two things: first, to publicly guarantee the U.S. will never default on its debt.

It's a promise that, if made, would effectively strip McCarthy of any leverage he has in the debt ceiling process.

Second, Biden plans to ask McCarthy when House Republicans will release a "detailed, comprehensive budget." It's little secret that House Republicans are divided over which federal programs to cut in their broader effort to trim public spending. By pressuring McCarthy to release a detailed budget, Democrats hope to spotlight these divisions.

McCarthy scoffed at the memo.

"Mr. President: I received your staff's memo. I'm not interested in political games," the House speaker wrote on Twitter shortly after the memo was released. "I'm coming to negotiate for the American people."

But while McCarthy may say he is coming to talk, Biden has repeatedly said he will not negotiate with Republicans over the debt limit under any circumstances. This is despite the fact that Biden needs Republican votes, and McCarthy's support, in order to move debt ceiling legislation through the House.

McCarthy took aim at Biden over this, too.

"It's irresponsible to say as the leader of the free world he's not going to negotiate," McCarthy told reporters in the Capitol on Tuesday. "I hope that's just [Biden's] staff and not him."

Instead of tying government spending cuts to the debt ceiling vote, the president wants to deal with GOP demands in separate budget negotiations later this year.

For House Republicans, that's a non-starter. They view a vote to increase the government's borrowing power and their demands for cuts to government spending as inextricably linked. They equate the U.S. government to a family with maxed out credit cards that needs to scale back its household spending.

"We need to sit down and have a responsible adult conversation like families do," House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, R-La., said Tuesday at a press conference in the Capitol. "Because if a family maxes out the credit card, they're not just going to go get another credit card."

"You're going to pay your debts," said Scalise. "But you're also going to have a responsible conversation about how we stop this from happening again."

To be clear, the debt ceiling does not operate like a consumer credit card. Raising the debt limit does not clear the way for any new spending, it merely allows the government to cover its preexisting commitments.

Complicating McCarthy's task on Wednesday is the fact that all GOP caucus members do not share his belief that the government must raise the debt ceiling. Several fiscal hardliners in the House have already made it clear they're willing to force a default on the national debt if they don't get massive spending cuts in return for passing it.

But it comes with a catch: Any bill that the House approves must also be able to win 60 votes to pass the Democratic-controlled Senate. There, the type of draconian spending cuts sought by far-right House Republicans would have no chance of passing.

On Wednesday, the Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York reminded the House speaker of his challenge.

"For days, Speaker McCarthy has heralded this sit-down as some kind of major win in his debt ceiling talks," Schumer said on the Senate floor. "Speaker McCarthy, if you don't have a plan, you can't seriously pretend you're having any real negotiations."

McCarthy's task of uniting his unruly caucus behind one plan would be difficult under any circumstances. But it's all the more challenging because his majority in the House is so narrow.

If he were to try to pass a House debt ceiling bill with only Republican votes, McCarthy's margin for error would be razor thin. He could only afford to lose four members of his caucus and still reach the 218-vote majority needed to pass the legislation.

He could also try to craft a debt ceiling bill that would pass with votes from more moderate Republicans and a large bloc of Democrats.

Betting on members of the opposing party to bail him out would be risky. But not as dangerous as failing to lift the debt ceiling altogether.

For both Democrats and Republicans, the worst case scenario would be an unprecedented government default on its debt that could halt daily operations within the federal government and cause turmoil in equity markets and the broader economy.

A Moody's Analytics report last year said a default on Treasury bonds could throw the U.S. economy into a tailspin as bad as the Great Recession. If the U.S. were to default, gross domestic product would drop 4% and 6 million workers would lose their jobs, Moody's projected.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has already invoked so-called "extraordinary measures" to avoid default. Yellen has also pointed to early June as the date by which those measures will run out, and by which Congress must act to raise the limit or face dire consequences.

Going into Biden and McCarthy's meeting, the absolute necessity of raising the debt ceiling may be one of the few things they agree upon. Yet with several months to go until the risks become more dire, there is little expectation that Wednesday's sit-down between Biden and McCarthy will yield any breakthroughs.

Instead, the real significance of the meeting may be that it will offer the House speaker and the president, who do not know each other very well, their first chance to start building some kind of working relationship. But if this week was any indication, cooperation is still a long way off.

Biden on Tuesday called McCarthy a "decent man," but suggested he is beholden to the far-right wing of his party.

Speaking at a Democratic National Committee fundraiser in New York, Biden took aim at the deals McCarthy made with conservative holdouts in order to be elected House Speaker. He called the agreements "off the wall."

The party that McCarthy leads today "is not your father's Republican Party," said Biden. "This is a different breed of cat."

It remains to be seen whether McCarthy can herd all of the cats that Biden characterized into the same pen. And if he can, whether the president will come to the table.