It’s early Saturday morning -- so early, the sun isn’t quite up -- but the race has already begun.

Piling out of the car, equipment in hand, the three competitors receive confused side-ways glances from the only other people up that early, two Trinity River kayakers. But these three aren’t out for a leisurely float down the river, but to win the cutthroat competition of bird watching.

Greg Cook has been training since he was a young boy. The slightest movements in a distant tree or the quietest chirps in a tall branch are sure to instantly catch his attention.

Steve Glover and Susan Thrower join Cook in the hunt for as many bird species as they can find in the county during the Fort Worth Audubon Society’s Scavenger Hunt.

The scavenger hunt is one of several bird watching events organized by the Audubon Societies in the Metroplex. In the winter, there’s the Christmas bird count -- where birders compete against each other, keeping a tally of every bird they see. And, in the fall, Tarrant and Dallas county birders go head-to-head in birding competition.

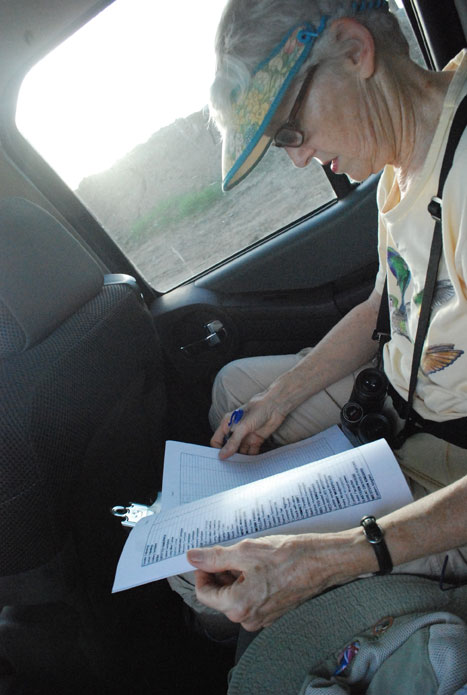

In this scavenger hunt, birders divide into small teams and receive a list of 158 birds. Each bird has a point value (between one and five) based on its frequency, with extra points for birds not on the list, and a deduction for not spotting that more common species. Cook’s team, the Crispy Caracaras, won with 168 points thanks to a boost from two birds not on the list.

Though everyone was cordial at the hamburger joint after the scavenger hunt, Cook admits he came to win just as much as he did watch the birds.

“The competitive part is what I enjoy,” he said.

Cook is no casual birder. His tally of all the bird species he has seen, or “life list,” recently exceeded 700. Somewhat of a threshold for serious birders, 700 shows years of birding experience and travel. He’s visited every state but Hawaii and Vermont to spot the next rare bird.

“Pretty much that’s why I go everywhere I go,” he said. “I want to see as many birds as I can in the U.S. and Canada, and then I’ll worry about going outward.”

Cook’s long list -- and edge in the scavenger hunt -- doesn’t always come from seeing the bird. He’s studied birdcalls in books for years, and even has a CD collection full of birdcalls, like a Rosetta Stone for birds.

“If it’s a bird that occurs in the U.S. I can identify it,” he said. “I also grew up in Pennsylvania, where all the birds are in the heavy forest so the ears are essential. You don’t see half the birds."

Many of the birds Saturday were heard and not seen, or at least not seen very well. Still, for the spotting to count, at least two birders have to be able to identify it. Birdcalls filled the air as the seekers walked along the River Legacy Trail and shouted out the names of species as they walked.

After River Legacy, the birders headed over to the Village Creek Drying Beds to pick up some birds that live in a wetter habitat. The area is an inactive solid waste treatment -- indicated by the particular smell recognized upon entry. The casual naturalist would spot ducks and a mute swan, but an experienced birder will find several species.

Many of the teams spent most of the day at the Drying Beds, but an experienced scavenger hunt birder knows covering a lot of ground is key. Thrower has participated in four of the seven scavenger hunts, and even won a few.

"When you’ve got the time deadline, you have to ask: How many points is that bird?" she said. "Is it worth the hour drive?"

One of those birds was the Monk Parrot, and these birders knew exactly where to go to find it.

The birders drove all over Tarrant County to find everything they needed, from one county line to the other. Cook and Trower's edge in the competition also came from knowing exactly where some birds make a home.

Not surprisingly, there are not a lot of birding locations in the Metroplex, so even Cook's apartment complex was one stop on the list. Glover who moved to the area from the bay area in California about a year ago is still getting used to it.

"There's only one birding spot in Tarrant County," he said. "The only place I've ever seen birders is in the drying beds."

Thrower said the grassland birds are suffering the most. Development -- not just in the Metroplex, but across the country -- hurts many different species. The Bobwhite, which nests on the ground, is becoming increasingly difficult to find because of fire ants and feral cats, she explained as the team drove through a subdivision in the southern part of the county.

"Like, the Meadowlark used to be just so plentiful," she said. "You'd drive down roads like this and they'd just be everywhere, but now they've lost so much habitat there's fewer and fewer."'

The birders agree that the scavenger hunt list, which is 10-years-old, needs a revision. Cook is quick to point out that bird populations naturally change over time as well, and that he's working on an updated list. He said other animal populations often affect bird populations; for example, more rodents will increase the number of hunting prey birds. Cook added there are also some invasive species like the Eurasian Collard Dove.

"Here, about 10 years ago, it would have been a bird that you'd called everybody to tell them that you'd had one it was so rare," he said. "But now they're everywhere."

But there is some silver lining. On the other side of the Metroplex, in Kaufman County, there's a new birding spot that is all the buzz.

Though it was off-limits for the scavenger hunt, Cook said it is his favorite spot to bird watch.

"It's John Bunker Sands Wetlands, and that's by far the best birding area around," he said.

With the day almost over, the team is only missing a couple more of the "must have" birds: the Red-Shouldered Hawk and the King Fisher. The King Fisher is one that Cook isn't entirely sure they will find, he says they are a bird that "you stumble upon." But the searchers don't lose hope and head back to the drying beds for one last lap before the hunt ends at noon.

They may be expert birders, but Cook says birding can start anywhere and at any age.

"If anybody cares about any birds that’s good, because that means if you care about one bird you’re going to care about the habitat, and everything else for all the other birds," he said. "If you’re out and about you’re doing good."