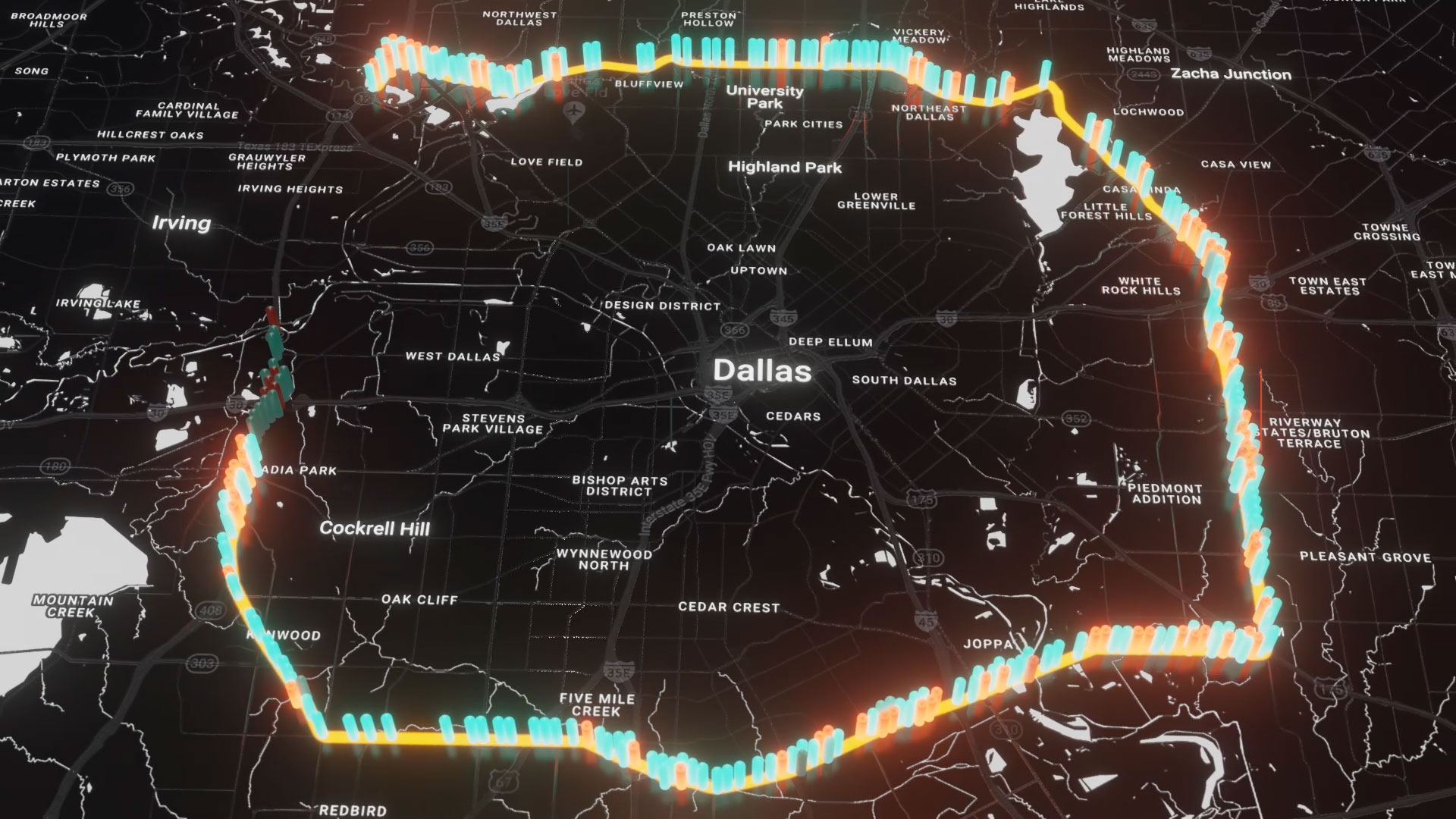

As NBC 5 Investigates revealed in previous reports, the city of Dallas has the highest traffic death rate among U.S. cities with more than one million people. Every week last year, about four people were killed in car crashes in Dallas, and another 23 were seriously injured.

We wondered what it might look like if Dallas more aggressively implemented "Vision Zero," the safety strategy the City Council said it wanted to use to create safer streets and reduce traffic deaths. With that solution in mind, NBC 5 Investigates senior investigative reporter Scott Friedman traveled to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada -- a place where, on most weeks, no one dies in a car crash, and the city credits "Vision Zero" for saving lives.

The province of Alberta is sometimes referred to as "the Texas of the North." It's a region not unlike our own and is known for producing oil, pickup trucks, rodeos, big cities, and ranches. In recent years, though, Edmonton has been successful in driving down traffic deaths and injuries with an aggressive road safety strategy.

While the Dallas metropolitan area is larger than Edmonton, the two cities themselves are similar in size with about 1.1 million people in Edmonton and approximately 1.3 million people in Dallas. Last year Edmonton had just 14 traffic deaths while Dallas had 228.

So maybe Dallas could learn something from this Canadian town -- a place where crosswalks can be installed diagonally and may resemble something from the Land of Oz.

The diagonal crosswalk called a scramble crosswalk, allows pedestrians to cross the street either from corner to corner or diagonally through the center of the street. Traffic engineers programmed traffic lights to briefly halt cars in all directions, briefly giving pedestrians full use of the intersection. Right-hand turns are also temporarily prohibited, preventing drivers from turning into people in crosswalks.

Edmonton installs scramble crosswalks in spots where crashes have hurt and killed pedestrians. In one scramble crosswalk visited by NBC 5 Investigates, city traffic engineer official Tazul Islam said there were no collisions involving pedestrians in that location in the two years since the crosswalk was installed.

The scramble crosswalks are just one small part of a Vision Zero plan Edmonton adopted in 2015. Over the next six years, the city said traffic deaths declined by 50% and severe injuries by 30%. When you ask city leaders how they achieved those reductions, the answer often includes one word -- data.

Edmonton's Vision Zero team uses data to first identify where people are injured and killed the most and then they attack those spots with everything from high-tech traffic enforcement to radical street redesigns.

In some locations, city leaders have taken away a lane of traffic to slow drivers down. The extra space can then be used to create dedicated bike or pedestrian lanes in high-traffic areas.

In busy pedestrian neighborhoods, they've narrowed roads to slow traffic speeds. From a safety standpoint, Ryan Kirstiuk, the city's neighborhood planning director, says narrowing roads improves sightlines for people and that drivers will instinctively slow down when they turn into a neighborhood where the road is tighter. This can be more effective in reducing speeds, Edmonton officials said, than simply lowering the speed limit, which some drivers may still ignore.

If the city cannot build a narrower street in a problem spot right away, traffic engineers use temporary tools to extend curbs into the roadway creating a narrower space for cars. These temporary curb extensions, city officials said, can be installed in a day.

"The narrowing of the road by this curb extension just makes people a little bit more subconscious or conscious about, OK, I better slow down because there's something going on here," said Rupesh Patel, manager of Safe Mobility at the City of Edmonton.

Those curb extensions have helped in Paul Kyler's neighborhood, on a street locals dubbed "The Speedway."

"We've had a number of casualties on this road because of speed," Kyler said.

Kyler worked with his neighbors and Edmonton's "Street Lab" program that connects families with city traffic engineers. In his neighborhood, the temporary curb extensions were installed initially as a test.

"We'll hear their concerns, and then we'll work with them to implement traffic calming measures," said Patel.

When enough data has been gathered on the temporary measures, the city then considers pouring concrete curb extensions to alter the shape of the road long-term.

"Once we get enough feedback, seeing how they work, if they work, they put in a more permanent solution, which we're actually getting here," Kyler said.

All over Edmonton permanent concrete curb extensions can be found shortening the distance for pedestrians to cross the street while also encouraging slower speeds near intersections, where the extensions give drivers a feeling of entering a narrower space. The city is also raising many crosswalks to make them more visible to drivers and even partnering with schoolchildren to paint crosswalks bright colors in school zones to increase visibility.

"As drivers are approaching the crosswalk, they can see it from a distance away and it's been well received by the community," Patel said.

But reshaping and redesigning roads is only part of the plan.

Neon-yellow automated speed enforcement trucks are slowing drivers in spots where crashes happen most. Peace officers monitor from inside the trucks as radar on board automatically clocks speeds, cameras snap photos of speeders, and tickets are then sent in the mail.

"We want people to slow down immediately. Right?" Fran Mawson-Dalmer, City of Edmonton Traffic Safety Coordinator, said of the yellow trucks. "It's a really good tool and it's proven effective year after year. For our Vision Zero strategy."

The city said crashes have come down more than 30% on streets where the trucks are used. Under local Alberta laws and city of Edmonton policy they can only be used in limited spots with a history of crashes, and those locations must be published in advance. In Texas, those cameras would not be allowed as state law prohibits automated traffic enforcement.

"That's why our vehicles are bright yellow, right? We're not hiding behind the trees, we're out in the open. People can see us because we want them to slow down," Mawson-Dalmer said.

The automated speed enforcement vehicles also assist law enforcement, saving time by reducing the need for traffic stops which can also lead to sometimes risky interactions with drivers.

Still, as you can imagine, not everyone in Edmonton was thrilled with the idea of slowing down traffic. City Councillor Andrew Knack said city leaders have faced opposition especially when they voted to lower speed limits city-wide.

"There was this fear that, you know, the traffic would be at a standstill," Knack said. But city engineers responded to those concerns using data to show that most drivers would barely notice a minute or two added to their commute while the slower speeds would reduce deaths. Knack said he hardly hears any criticism now that the lower limits are in place.

"Almost everyone has moved on and realized how much better and how much safer that's made our local communities," Knack said.

"Nobody likes change. But at the end of the day, when you see the results and when you can feel the actual extra safety, it's worth it," Kyler said.

What Edmontonians told NBC 5 Investigates is that all of the data has not only helped fix problems, it's also been a vital tool in getting people to buy into the Vision Zero strategy.

There's power, they say, in numbers showing things like crazy-looking crosswalks working to reduce injuries and deaths.

"When you tell the other side of the story of how it is saving life, protecting them. Then people understand why we are doing what we are doing," Tazul said.

Edmonton has dedicated money and staff to making Vision Zero work. They have a full-time group focused on the plan and invest about $180 million per year in Canadian dollars redeveloping neighborhoods with a heavy Vision Zero focus.

In Dallas, the city council initially only allotted about $1.7 million to Vision Zero so far, and most staff working on the plan were also assigned to other duties. The Dallas Transportation Department hopes for more funding after next year's bond election. As NBC 5 Investigates has reported, it took Dallas city staff almost three years to develop a Vision Zero plan, and most of the planned action items for 2023 were not completed or not started with just eight weeks remaining in the year.

In addition to not being able to use automated traffic enforcement, Dallas does face other challenges as well. As we previously reported, some of the deadliest streets in Dallas are also state highways which means the city would have to convince the Texas Department of Transportation to help reshape those roads.

In our next report, we'll show you why some safety advocates fear TxDOT's policies could be a roadblock to safer streets in Dallas.