This fall, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art reintroduces a modern Texas artist and investigates how people became comfortable with photography in the nineteenth century. Texas Made Modern: The Art of Everett Spruce and Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography are now on view at the Fort Worth museum through November 1.

Everett Spruce was born and raised in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, but paintings revealed his heart was always in Texas. Texas Made Modern explores the range of Spruce’s career, featuring works from the 1920s to the 1970s.

His surreal landscapes of West Texas, mature figural paintings of folk culture and late abstract visions made him one of the most exciting artists, only to be overlooked with the rise of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

“At midcentury, in the middle of the 20th century, Everett Spruce was the best known, most acclaimed artist working in Texas, but as it often happens when the art history canons get written, a lot of Texas artists are forgotten. The hope of this exhibition is to really look at his career and how talented he was as a painter and how dedicated he was to Texas,” Shirley Reece-Hughes, the Carter’s Curator of Paintings, Sculpture and Works on Paper and organizer of this exhibition, said.

A member of the fabled Dallas Nine, Spruce used modernism to communicate the spirituality of nature. “The focus of his work is really this communion with nature. What differentiated Spruce was that he was very open to modernist ideas. He could evoke otherworldly realms,” Reece-Hughes said.

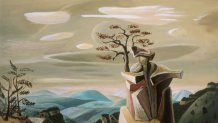

In Arkansas Landscape, the mountains are dreamy and clouds swirl in the sky, but there is a nod to Texas. “Even in this supposed view of Arkansas, on the left, you have mesquite trees from Texas,” Reece-Hughes said.

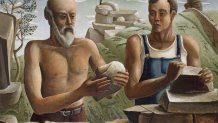

Mending the Rock Fence is one of the few paintings featuring people. Inspired by Renaissance artists, Spruce paints people as saint-like figures, indicating a reverence for work in a natural landscape. “It reflected his deep religiosity in nature and how powerful he believed that was,” Reece-Hughes said.

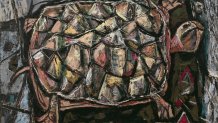

With Big Turtle, Spruce approached animals with the same veneration as he did landscapes, using sophisticated and dynamic patterning in his brushwork. “He took his landscapes into wildlife and ecology. He really was an amateur naturalist and an amateur ecologist. He really understood nature and he wanted to communicate that,’ Reece-Hughes said.

The Texas coastline inspired Spruce to push himself. Broken Jetty is more abstract. “The static qualities of his early work gave way to the looser, almost ephemeral, fluid and fleeting qualities,” Reece-Hughes said. “He really moved beyond what his contemporaries were doing because he never stayed static. He kept challenging himself.”

Before Instagram, there were cabinet cards. Acting Out explores the whimsical and curious world of 19th-century portraiture through more than 100 photographs, many on view for the first time. “Acting Out is really about how we came to embrace photography in everyday life,” John Rohrbach, Senior Curator of Photographs at the Carter, said. “This is really a show not about high art. It is not about major photographers and their services to art. It’s really about all of us.”

Cabinet cards are photographs measuring 6.5 inches by 4.25 inches, approximately the size of a smartphone’s screen. These cabinet cards were larger than previous personal photographs, giving people more space to create detailed presentations of their lives. They were the perfect size to display on a cabinet, bookcase or to mail to friends and family. Photographs were sold by the dozen, ranging in price from $2 to $5 a dozen or $40 to $50 in today’s money.

People went to a photographer’s studio to have their picture made. “You went into the studio, you often set yourself up in front of an elaborate backdrop and performed for the camera,” Rohrbach said. This exhibition features a rare studio backdrop from the cabinet card era.

Napoleon Sarony became the favorite photographer of Broadway actors and celebrities. “Sarony did it basically by faking instantaneity. By doing that, he became the go-to photographer for New York for much of the last of the 19th century,” Rohrbach said.

Most photographers could not replicate Sarony’s effortless immediacy and they wanted to draw customers into their studios frequently. “They gave out special coupons out in the streets, they provided special frames for cabinet cards that you could buy directly from the photographers,” Rohrbach said. Photographers also offered overlays and customers were welcome to bring props.

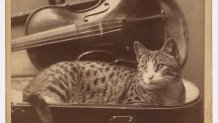

As cabinet cards grew in popularity, people reimagined how they wanted to portray themselves. “They photographed their families in all sorts of styles, in all sorts of conveniences. Why put your child in your lap when you can show off your new baby carriage? Why not show your family eating breakfast? Why not show your favorite pet?” Rohrbach said. “The exhibition presents a whole run as if you’re walking through a family album from babyhood all the way to death.”

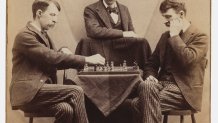

Eventually people were using photography to do more than mark important milestones. They began to play, photographing themselves playing chess against…themselves. “All of this is a game. This is all a façade. We think of photography as documenting the world, showing us reality. But at the end of the nineteenth century, people all understood photography was something that not only showed what people looked like, but also a release to games,” Rohrbach said.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

Learn more: https://www.cartermuseum.org/