At the African American Museum in Dallas, visitors learn the American Old West was really the Black West. “Black Cowboys: An American Story” expands the story of Hollywood’s favorite heroes to include the Black men and women who worked on the cattle drives and ranches. The exhibition is on view at the Fair Park museum through April 15.

“In our popular culture, we’ve highlighted the John Waynes, the Clint Eastwoods, and the Roy Rogerses and ignored the people who were 30% of the cowboys of – as they called it – the Old West between the 1860s and 1890s,” said Dr. W. Marvin Dulaney, the museum’s deputy director and chief operations officer.

Featuring more than 50 artifacts, photographs, documents and films, the exhibition, organized by the Witte Museum in San Antonio, shows how Black cowboys lived their lives and the role they played in this legendary chapter of American history.

“It tells a different story from what we typically learn in popular culture,” Dulaney said.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

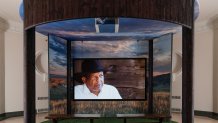

At the center of the first section of the exhibition is a film about Hector Bazy, a Black cowboy born into slavery on a plantation in Grimes County, Texas in 1851. He was 14 years old when he began working as a cowboy. He remembers the cowboys made no racial distinction on the trails.

The film in the exhibition is based on the 1910 autobiography he wrote about his harrowing existence as a Black cowboy. Actor and playwright Eugene Lee play Bazy in the film.

The Scene

“He tells basically the everyday life of what it was like to be a Black cowboy in 1865 through 1890s,” Dulaney said.

Black cowboys became a common part of American life as early as the colonial era when white colonists were looking for economic opportunities in North Carolina.

“They were looking for a way to make money. They would eventually discover they could grow rice to make money, but before that, they engaged in naval stores, lumbering and herding cattle. And they brought in Africans from West Africa who had a tradition of herding cattle in West Africa to herd cattle in the Carolinas,” Dulaney said.

Eventually, the cattle trails moved west, and Black cowboys did the work as part of their enslavement.

“This was hard, dangerous work and guess who does the hard dangerous work in our country,” Dulaney said. “It’s an experience of enslavement as well as freedom.”

After Emancipation, Black cowboys worked on and eventually owned their own ranches, honing their skills of taming and training horses, tending to livestock, and driving thousands of cattle on the trails across America. Many cowboys transferred their skills to work in other fields.

Jim Perry was respected as a top hand, expert roper, renowned cook and fiddler on XIT Ranch, a three-million-acre ranch near Dalhart, Texas. His fellow ranch hands believed he would have been promoted to ranch foreman if he had been white. Ben Kinchlow, an experienced horse breaker who rode herds up the trail to Kansas and Nebraska six times, became one of the first Black men to work with the Texas Rangers.

The exhibition shows how Black cowboys used their skills for performances in rodeos, music, and film. In 1964, Myrtis Dightman became the first African American to compete in the National Finals Rodeo, earning the nickname “The Jackie Robinson of Professional Rodeo.” Bill Pickett, born on Jenks-Branch, a Freedman Colony near Austin in 1870, worked as a cowboy and performer in rodeos and Wild West shows before becoming the first Black film star. Pickett was the first African American to be inducted into the National Cowboy Museum in Oklahoma City.

These performances and contributions to the entertainment industry are often overlooked.

“We’re correcting the record in telling the whole story,” Dulaney said

The exhibition highlights some women like Henrietta “Aunt Rittie” Williams Foster, who proudly worked cattle and rode horses along with men.

“There weren’t many,” Dulaney said. “They were there because they were wives and mothers and often accompanying some of the cowboys on the range and on the trails.”

Understanding how integral Black cowboys were to the economy shows how important they were to Texas history.

“Texas was sort of the center of the cattle driving, the ranches, and the Black cowboys being part of the Old West because most of the Black cowboys were here in Texas,” Dulaney said.

The African American Museum, Dallas is also hosting the 27th Carroll Harris Simms National Black Art Competition and Exhibition. The biennial competition is named in honor of Simms, an African American sculptor, ceramicist, and professor at Texas Southern University until his retirement in 1987. He died in Texas in 2010.

“We’re really happy to be able to honor his legacy and have this exhibition,” said Gerald Leavell, a Helen Giddings Fellow and assistant curator of the museum.

Judged by three art professionals, the competition awards $1,000 to one artist in each of these mediums: painting, photography, printmaking, drawing, and mixed media. The jurors select one artist as Best in Show. This year’s exhibition features almost 50 artists from a large field of applicants.

“We’re really excited to have been able to attract over 400 artists from across the United States to participate in this,” Leavell said.

The winners were announced on Friday, January 27. Three winners are from Texas.

PRINTMAKING: Hallelujah Anyhow, 2021; Steve Prince (Williamsburg, VA)

SCULPTURE/ASSEMBLAGE: Three Graces, 2022, Austen Brantley (Detroit, MI)

PAINTING: Homecoming, 2022, Assandre Jean-Baptiste (Cedar Hill, Texas)

PHOTOGRAPHY: Faded, 2021, Inyang Essien (Addison, Texas)

DRAWING: Perseverance, 2022, Manasseh Johnson Sr. (Converse, Texas)

MIXED MEDIA: Born and Reborn, 2022, Mayowa Nwadike (New York, NY)

BEST IN SHOW: Hallelujah Anyhow, 2021; Steve Prince (Williamsburg, VA)

Learn more: African American Museum, Dallas