For Ina Garten, queen of the kitchen and “engagement” chicken, store-bought is always fine — even when she’s having lunch with Hoda Kotb to discuss her new memoir, “Be Ready When the Luck Happens.”

At home in her Upper East Side apartment, Garten is preparing for her guest. She walks into the kitchen to pick out a spatula she then uses to remove two tuna sandwiches from their take-out containers. (She’d considered using her hands but decided that would ruin their beauty.) Carefully arranging their lunch on plates, the 76-year-old media darling pauses to separate the sandwich halves just so, ensuring they look as enticing as possible before artfully drizzling vinaigrette over the side salad.

Her process this afternoon is a small but crucial act of care. It’s clear it’s exactly this kind of love that’s paramount for Garten — but, as she tells Hoda, was decidedly absent from her childhood home.

Garten tells Hoda that mealtime growing up was simply “about getting dinner on the table.”

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

Watch Hoda’s sit down with Ina Garten in full below — or continue on to read more.

“It was broiled chicken, canned peas — it was never about flavor or feeling good or treating yourself,” she says of the years she lived in Brooklyn and then Connecticut with her parents, Florence and Charles Rosenberg, and her older brother, Ken Rosenberg.

Entertainment News

“There were no carbohydrates allowed” and “no fat” in their meals, she continues, adding that her mother, who trained as a dietitian, thought they were bad for you. “But she was also very extreme.”

There was also never any comfort food, she says. Even little joys like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were “forbidden.”

For the young girl who craved connection, life with her grandparents was an entirely different story, where food and love came in big portions.

In her book, Garten details the emotional (and metaphorical) hearth and home that Morris and Bessie Rosenberg built.

“She was always cooking,” Garten writes of her paternal grandmother, “and like all good cooks, she was happiest when she was feeding people.”

She remembers Bessie as generous and good-humored, and says the couple created a warm atmosphere filled with relatives, friends, food and love.

It’s that feeling that Garten sought to emulate when she launched her Food Network show “Be My Guest” in 2022, where she hosts celebrities at her East Hampton estate for a home-cooked meal and conversation. Garten tells Hoda it wasn’t until she developed the show that she realized, through the concept, she was satiating her younger self’s craving for connection.

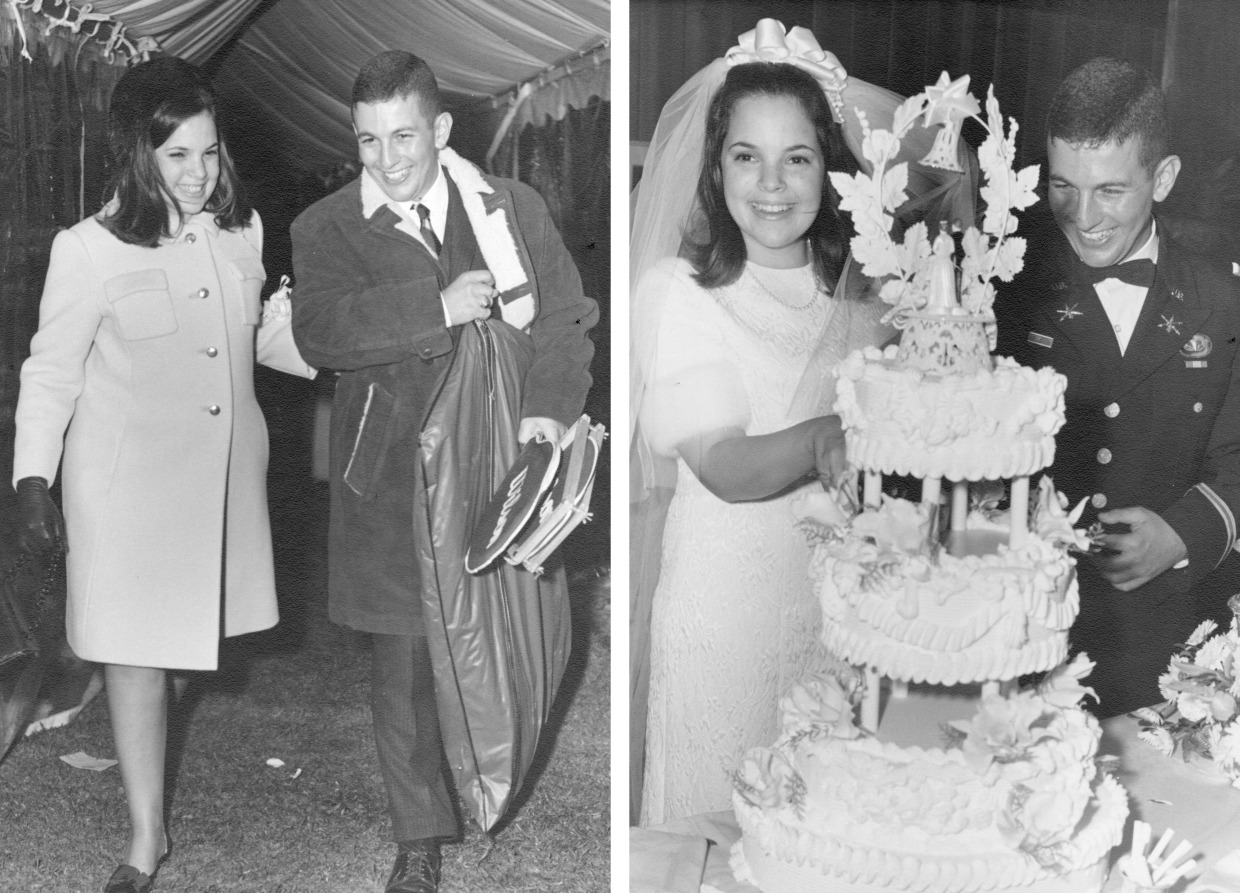

Ina Rosenberg was born on Feb. 2, 1948, in Brooklyn, New York. But if you ask the woman we have all come to know as the Barefoot Contessa, her life really began when she met now husband Jeffrey Garten on Dartmouth College’s campus in 1963, which is where her book begins.

“That’s when my life started,” she tells Hoda. “The life that I want to live, that’s when it started.”

While the author has published 13 cookbooks prior to her memoir, this one is hitting differently. She’s not used to being this bare with the public, and when she’s gotten comments from media and readers in the past, they’ve largely been about her recipes.

“I’m used to putting books out, but it’s, like, roast chicken,” she says. “This is like, ‘Woah.’”

Growing up a Rosenberg

While her upbringing ranged from sterile at best to terror-inducing at worst, she’s relaxed about diving in deeper with Hoda — leaning her forearm on the table with a soft smile as she listens to the TODAY anchor walk through stories of her life.

Garten tells Hoda her mother “would do the things that she knew a mother should do” — museum trips, getting nutrients into her kids’ bodies — “but none of it was done with joy or warmth or ‘I see you and I think this will make you feel good’ — and that’s what my whole world is about (now).”

She’s not sure her mother, Florence, was capable of loving her children or forming relationships.

“And I think that scared her,” Garten says. “I can really empathize with how scary that is — to try and have a relationship. But as a child, it was very hard to have a mother you couldn’t have a relationship with.”

There were “no hugs and kisses in my family,” the author says with a laugh.

Whenever she got sick, “I was in my bedroom with a bell. If I needed something ... she’d come and give it to me and then leave.”

“Most mothers would want to take care of you when you were sick,” she adds. “My mother didn’t want to be anywhere near me because she was a germaphobe and didn’t want to be in the room.”

Even little things like a skinned knee went unmentioned and uncomforted.

As the two speak about what a mother’s love looks like to them, Hoda pauses to emphasize that Garten had just said she wasn’t sure her late mother ever loved her.

“She didn’t understand me, actually,” Garten replies. “I’m sure about that.”

She has come to understand that her mother likely thought it was safer for herself “to be on her own and have me somewhere else.”

Safety was also top of mind for Garten as a kid, but she was more concerned with physical danger.

“My father had very strict views of what we should do,” she says, listing out straight As and a commitment to tennis as parts of his requirements. “Anything ... that slightly deviated from that was met with extreme anger.” Using an open hand to demonstrate a hitting motion, Garten tells Hoda this included physical abuse.

“I actually stayed in my room to stay safe,” she says, later adding, “I think I was terrified that he was going to kill me.”

Even still, Garten tells Hoda it could have been worse. “People had much worse childhoods than I did,” she says. “I mean, I had lots of opportunities and I had wonderful friends.”

Garten says she was popular at school and had no trouble in the dating department.

“It’s just, in the house, it was a scary place,” she adds, laughing again at the dichotomy.

Now, her childhood friends tell her they never had any idea what was going on back then; she says the abuse never got to the point of leaving bruises that needed explaining.

“But they also knew that they never came to my house,” she says.

The businesswoman, best-selling author and TV host says she’s astonished that she “didn’t have the courage as a child to fight back — I just tried to disappear.”

“That’s what most — I think most kids would have done,” Hoda says with assurance.

Jeffrey, her cheerleader

Meeting Jeffrey was a turning point for how Garten saw herself in the world.

“He just took total delight in me,” she tells Hoda. “He made me feel so smart and funny and thoughtful and wonderful, and he was too.”

Garten calls younger Jeffrey “somewhat forward-thinking” as he “always encouraged me to have my own life,” telling her early on in their relationship that she should figure out what it was she wanted to do.

“If you don’t, you won’t be happy,” she remembers him telling her. “I was just stunned, because it never occurred to me that I would do anything.”

Garten says her mother thought marrying Jeffrey was a huge mistake.

“My mother walked into the room and said, ‘I think this is a terrible idea,’” she remembers of the day her parents drove up to see her at Syracuse University after receiving a call from Jeffrey they assumed was preceding a marriage proposal.

“I just pulled myself together,” she remembers, placing herself in her sophomore year living quarters. With as much love as she could manage to conjure up, she told her mother for the first time ever, “I don’t care what you think.”

Her father, on the other hand, said marrying Jeffrey was “the smartest thing you’ve ever done,” Garten says with a smile. The couple wed before she graduated from college as Jeffrey was joining the army.

That bout of courage to stand up to her mother has stayed with Garten well into adulthood. As Hoda points out, she’s been a trailblazer in her career, initially disregarding the advice of publishers who thought including photos and fewer recipes in her first book was a huge mistake.

“Who needs 250 recipes?” Garten says, talking about the standard for cookbooks at the time. “So I wrote the book I wanted to write, and (to) everybody that tried to pull me off my game I just said, ‘This is what I’m going to do,’ and if it’s a bad idea they’ll never have to see me again anyway — it won’t sell.”

A baker’s dozen titles later, it’s safe to say Garten’s gut was right.

Between the Barefoot Contessa store, book deals, TV shows and more, Garten’s career has taken turns she never could have expected.

“I have no idea what’s ahead, and I don’t need to know,” she says of her future and what’s next.

Whatever she’s doing, it’s clear one through line remains: her husband.

A marriage of their own

Before they became couple goals, as Hoda points out, the Gartens had to create their own model for marriage. It started with their approach to children.

When they first got married, Garten assumed they would have “a traditional relationship,” which included kids.

But in her 20s, she resisted the idea. “I was like, ‘Why would I want to re-create that nightmare that I just came from?’”

She couldn’t imagine how a life at home with children could be anything different from what she had experienced. At 25 years old, after pushing those discussions further down the line, she finally decided against having kids altogether.

Today, the mother of all things freshly baked could not be happier with that choice.

“I can’t even imagine,” she says. “I just don’t know if I would have been a good parent, and I love my life the way it is now, and I couldn’t possibly have had it if I had children.”

As a couple, she says, “he was always the husband and I was always the wife.” Over time, though, she realized what she really wanted was a partner.

Their respective roles chafed once she purchased her Westhampton specialty foods store, Barefoot Contessa, and left her government job — and for stretches of time, her husband — in Washington, D.C.

After a brief separation and conversations about what they each wanted their marriage to look like, the two were able to grow together, rather than apart.

“Turns out, I love making dinner!” she tells Hoda. “I just didn’t want somebody to expect me to make dinner.”

The separation helped them reset.

“We reintroduced ourselves on a different basis,” she says. “And I remember thinking to myself, ‘Oh my God, I’m falling in love with somebody who happens to be my husband.’ It was an incredible experience.”

A beloved life

By the time her parents died, Garten says she had “separated from them so much” their passing didn’t have an “enormous impact” on her.

When they each died, she tells Hoda, “I didn’t really lose much.”

“I was surprised that I was sadder about my father than I expected to be, but my mother and I never had anything,” she says.

Garten’s relationship with her father, Charles, changed drastically once she got married.

“It changed his view of me,” she says, “because he saw me through Jeffrey’s eyes.”

She tells Hoda that Charles eventually apologized to her at one of her book parties — “It meant everything to me.”

Hoda takes a minute to let that sink in. “Can we just pause and just reexamine that for a second? So now, your dad, who’s known you since you were born, saw you because a man loved you.”

Garten confirms: “Isn’t that extraordinary?”

This was quite a departure from the stance he took while she was young.

“I think I was about 13, and he was mad about something, I have no idea what,” she recalls. “And he said, ‘Nobody will ever love you.’”

Immediately after those words leave her mouth, Garten smiles and explains what she calls the “great cosmic joke” of her life: “And do you know what I love? I love walking up Madison Avenue and every other block somebody leans in and says, ‘I love you.’”

“Oops!” she says, still laughing in her signature chuckle. “I guess he was wrong.”

How great is that?

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from TODAY: