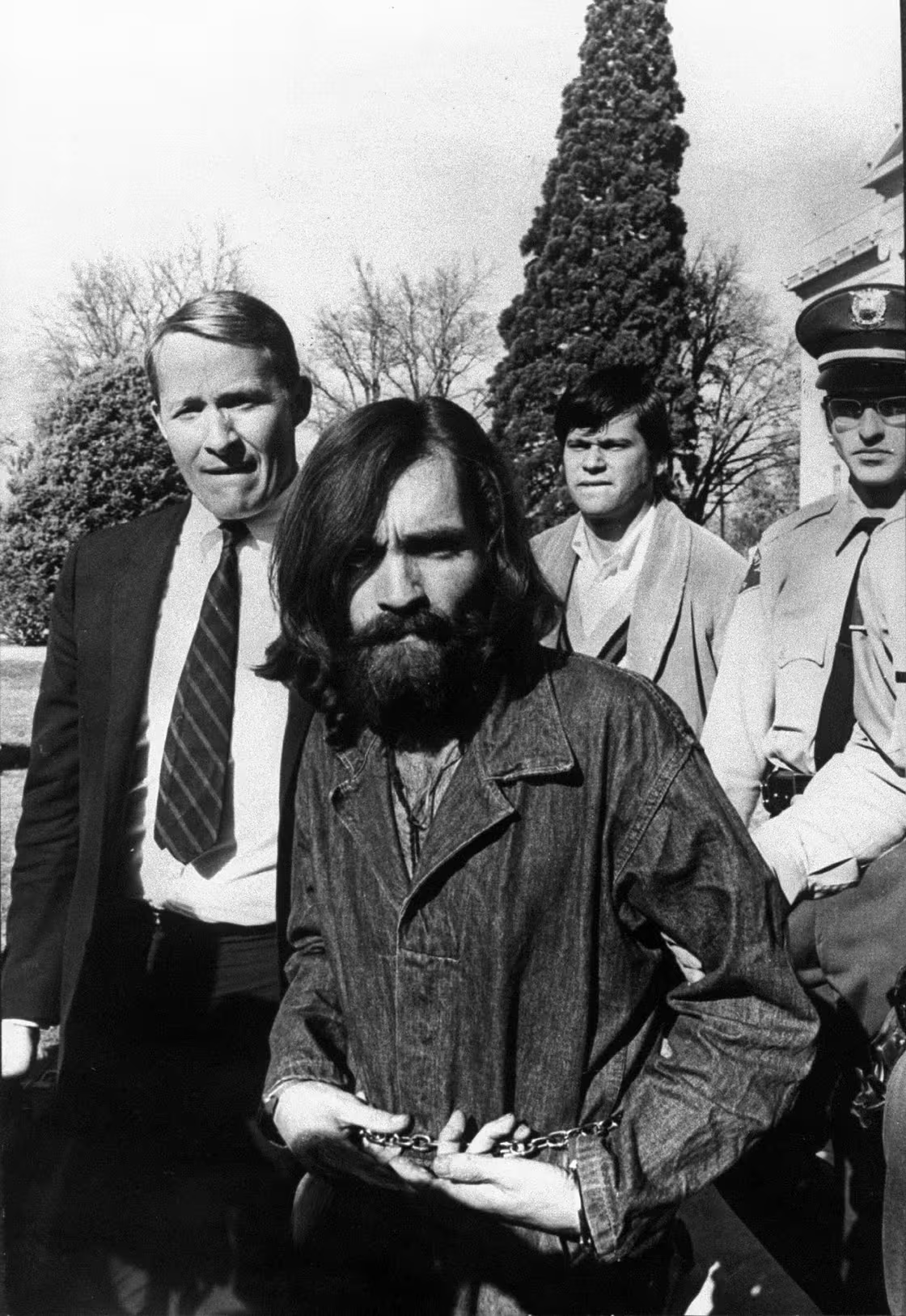

Fifty years after the Manson Family killings, the name Charles Manson still evokes a strong image — that of a shaggy-haired cult leader who spoke provocatively about mass murder.

“There’s no need to feel guilty. I haven’t done anything I’m ashamed of. Maybe I haven’t done enough,” Manson said in a 1987 interview with TODAY at California’s San Quentin prison. “Maybe I should have killed four, five hundred people, then I would have felt better. Then I would have felt like I really offered society something.”

Manson, whose followers committed a series of brutal killings in the late 1960s, is known for his infamous crimes. What’s less known is who Manson was behind the scenes, when he was not being interviewed or making erratic outbursts in the courtroom.

A new Peacock docuseries, “Making Manson,” out Nov. 19, features 20 years of never-before-heard recordings of Manson’s private phone conversations from prison. Peacock is owned by TODAY’s parent company, NBCUniversal.

Get top local stories in DFW delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC DFW's News Headlines newsletter.

More than 100 hours of audio recordings were provided by John Michael Jones, a man who says he first wrote to Manson in an effort to get his signature, then struck up a decadeslong relationship with him, according to his interview in the documentary. They stayed in touch until Manson’s death in 2017.

These recordings “gave us a candid conversation that we’ve never seen. We’ve never seen Manson without the mask before,” the documentary’s director, Billie Mintz, tells TODAY.com.

Entertainment News

Mintz says the documentary, which also features several interviews with former members of Manson’s circle, is not meant to exonerate Manson, but to add dimension and context to the widely accepted narrative about him. The documentary also includes the perspective of a forensic psychologist who analyzes Manson’s tapes.

“I’m not saying that I have sympathy for Manson,” Mintz says, “but by humanizing him, we understand a lot more of what led to these tragic events, and we learned a lot more about ourselves.”

Read on to learn more about Charles Manson, and what is revealed in “Making Manson.”

Who was Charles Manson?

Charles Manson was a cult leader who was convicted in murder in 1971 after his supporters committed a series of violent murders under his influence.

Manson’s followers, many of whom were teenage girls drawn to communal living and other 1960s counterculture ideals, have opened up about how he exerted power over them.

“He was always needing to be in control, and that came from having all control taken from him at a very young age, and being helpless,” former follower Catherine Share says in the documentary.

Share was not involved in the Tate-LaBianca murders but served five years for involvement in a Manson Family robbery and later served a sentence for participating in a credit card scheme, per AP.

“And a man does not want to be helpless, and he’ll do anything not to feel that way again. He tried love for a while. He said, ‘Oh, that worked.’ And he said, ‘But fear is stronger.’”

Manson had a troubled upbringing full of trauma and abandonment, per NBC News, and he had frequent run-ins with the law from a young age. By the time he was 32 and released from a 10-year prison term in 1967, he had spent half his life in prison, Vincent Bugliosi — a true crime author and the prosecutor at Manson’s trial for the Tate-LaBianca Murder — estimates in “Helter Skelter,” a definitive book about Manson. After his release, he moved to San Francisco and began attracting members of a group he called the Family. Members of the Family would go on to commit murders at Manson’s ordering.

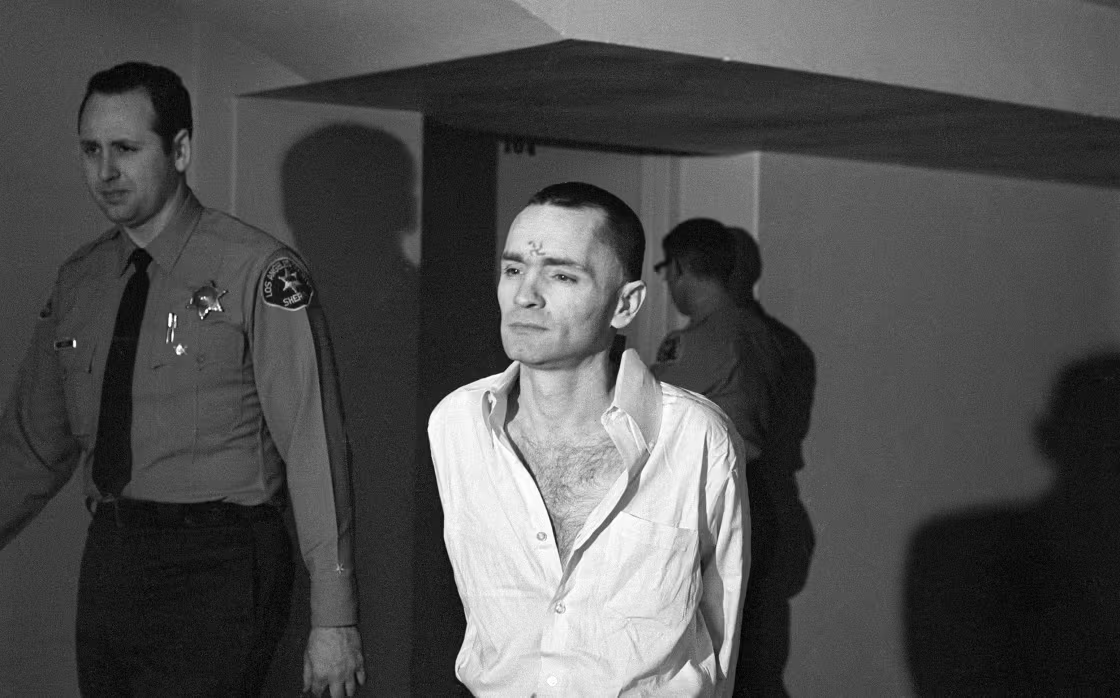

In April 1971, Manson was convicted on seven counts of first-degree murder, as well as one count of conspiracy to commit murder, for the deaths of seven people in what is often referred to as the Tate-LaBianca murders.

Members of Manson’s followers killed five people during the Tate murders, which took place on Aug. 9, 1969.

Actor Sharon Tate Polanski, the wife of director Roman Polanski, was one of the people killed during a gathering at her home. She had been 8 months pregnant. Also murdered were hair stylist Jay Sebring, Folger coffee heiress Abigail Folger and her boyfriend, writer Wojciech Frykowski and Steven Parent, who was visiting the caretaker of the Polanskis’ guest house.

The next day on Aug. 10, Manson’s followers murdered two more people, Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary LaBianca, at their home in Los Angeles, per the Associated Press.

While Manson was not physically present for any of these murders, prosecutors argued he held responsibility for the killings because he had known about the planned violence and had been closely involved in directing his followers to commit murder.

“The prosecution’s thesis was that Manson was vicariously liable for the acts of all the co-indictees,” according to a 1976 opinion issued in the Court of Appeals of California. “If the jury believed Manson to be a conspirator, aider or abettor he was culpable for all of the homicides regardless of who held the knife.”

Manson spoke to his role in the murders in the documentary. “I never said I was innocent. I said I didn’t break the law,” he said.

In March 1971, Manson and three of his followers, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten, were sentenced to death for their roles in the Tate-LaBianca killings, NBC News reported in his obit. Van Houten was charged in conspiracy for all the killings but for murder only in the LaBianca killings. Tex Watson was also sentenced to death later that year, the New York Times reported in 1971.

In December 1971, Manson received two further first-degree murder convictions for the July 1969 death of musician Gary Hinman, per NBC News, and the August 1969 death of stuntman and actor Donald Shea, per NBC News.

Bobby Beausoleil was convicted in the killing of Hinman in 1970 and remains in prison, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

In 1971, Manson devotee Bruce Davis was convicted in the killing of Hinman and Shea, and he remains in prison, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Steve Grogan was also convicted in Shea’s killing and was released on parole in 1985 after revealing the location of Shea’s body, per the L.A. Times.

The following year, Manson and his followers’ sentences were commuted to life in prison after California abolished the death penalty in 1972.

Manson remained incarcerated for the rest of his life. He died at 83 from natural causes on Nov. 19, 2017, at a hospital in Kern County, California, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Atkins, convicted on seven counts of first-degree murder, died in prison of cancer in 2009, NBC News reported. Watson and Krenwinkel, both convicted on seven counts of first-degree murder, remain in prison, per the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Van Houten, convicted on two counts of first-degree murder, was freed on parole in 2023, NBC News reported.

What is revealed in the Peacock documentary about Manson?

The “Making Manson” docuseries features never-before-heard audio recordings of Manson discussing his childhood, his followers and his criminal convictions.

In one recording, Manson claims that he murdered multiple people in Mexico.

“See, there’s a whole part of my life that nobody knows about,” he tells Jones in the tape. “I lived in Mexico for a while. I went to Acapulco, stole some cars. I just got involved in stuff over my head, man … got involved in a couple of killings. I left my .357 Magnum in Mexico City, and I left some dead people on the beach.”

He also argues that he was not responsible for the murders his followers committed and accuses the media of twisting his story.

“It’s the media. The media that starts selling that. They didn’t want to hear the truth. They wanted that hippie cult leader thing, man,” he says in one recording. “They didn’t give a f--- whether I did it or whether I didn’t do it. They wanted that vicarious thrill.”

Jones says in the documentary that he resonated with Manson’s difficult childhood experiences and describes building up a trusting relationship with Manson over the years.

“He found somebody he could be vulnerable to. I think that’s why Charlie gave me a lot of what we have on these tapes. And I think the longer I spent getting to know him, slowly that mask began to peel off,” he says.

Director Billie Mintz says it’s possible that Manson was lying at times on the tapes and attempting to manipulate Jones.

“I think that for sure, Manson wanted (Jones) to like him, and (Jones) wanted to like Manson,” Mintz says. “So I think there’s manipulation, but from listening to these stories, (Manson) didn’t have any reason to. He didn’t want to get out of prison. He wasn’t trying to exonerate himself. He literally says, ‘I’m a bad guy. I should be in prison, but I shouldn’t be in prison for this.’”

Mintz says the documentary places the tapes in context by interviewing a wide range of Manson experts and former followers to create “discourse where there was no discourse before.”

“We don’t say we know the truth, but maybe we give you a more nuanced, closer version of the story to the truth than you might’ve had before,” he says.

The documentary features interviews with multiple former members of the Family, including Dianne Lake, who was 14 when she met Manson. She wrote in her memoir “Member of the Family” that she did not participate in the Tate-LaBianca murders, and in fact testified against Manson and other members of the Family during the murder trial.

Lake, who was known by the nickname “Snake” in the Family, describes how Manson allegedly treated his female followers.

“He definitely used us and he definitely abused us,” she says. “I got hit and beat and raped, once, and I think the other girls probably did, too, but they kept it a secret.”

Share, another former Manson associate, recalls Manson turning “absolutely dark and electrified and menacing.”

The documentary also features interviews with Manson’s former cellmate and family members of the Family’s victims, as well as interviews with an investigative reporter, a forensic psychologist and a former FBI special agent and criminologist.

Near the end of the documentary, Jones defends his relationship with Manson.

“I’m not a fanboy. I’m a f------ human being with a heart who happened to befriend somebody that I didn’t expect to,” he says.

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from TODAY: